Friends of the Wildflower Garden

A web of present and past events

These short articles are written to highlight connections of the plants, history and lore of the Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden with different time frames or outside connections. A web of intersections.

This month we have answers for the curious. Why search for Live-forever? Why do honeycombs look so perfect? Icicles have certain shapes - why? Finally a bit of history, Eloise Butler and her problems with the swamp white oak - what is the future for that tree? - ending with a note on how Monarch escaped the fire.

This Month

Are Honeycombs as Perfect as They Look?

Why do Icicles Have Their Shape?

Eloise's Issues with White Oaks

Monarch Threatened with Fiery Death

Curiosity About a Name

The Friends website has information pages on almost 700 plants. The most often searched is the Live-forever, also called Witch’s moneybags, Purse Plant and Common Orpine and scientifically Hylotelephium telephium. It must be curiosity about those names that prompts these frequent searches. Here’s why.

The plant is a loner in the Upland at Eloise Butler. You may have never spotted it on your walks in the Garden as it is usually overgrown with taller more robust plants, but true to the name, it carries on from year to year. The spring rosettes are not difficult to spot as they precede the surrounding vegetation but flowering may be suppressed by the activity of the surrounding plants. Since it is not native, but an introduction of Eloise Butler, the Garden lets it alone, except perhaps, controlling the spread. It has been there since the late 1940s when Martha Crone moved it to the upland from the lower garden and then planted it several times. It was first established in 1927 by Eloise Butler. It is not native to Minnesota but to certain states in the east and to temperate Europe.

The Live Forevers are perennial plants with star-shaped flowers and coarse toothed leaves. This is a short erect plant, up to 2 feet high. The inflorescence is a compound cluster atop the stems. Pink flowers appear in compact cymes, each flower has 5 pinkish petals with pointed spreading tips. It spreads vegetatively from a white parsnip shaped tuberous root.

The strange names come from the leaves which are flat, thick, mostly elliptical and can be either opposite or alternate, very often with course teeth as shown in the photo. The upper and lower leaf surfaces can be separated by lateral pressure with the finger tips, creating a purse or pudding bag as the older common names of "Witch's Moneybags" and "Purse Plant" and "Pudding-bags" imply.

In the far distant past there was use of the leaves and the root for medicinal use. Culpepper (in 1653) refers back to older accounts for the usage as by his day it was little used.

We have here another example of why scientific names are preferred when referring to a certain species. Our preferred bible, Flora of North America, prefers Live-forever and American Orpine. USDA uses Allegheny stonecrop and our own Minnesota DNR simply uses Orphine.

Perhaps you may catch it in flower some late summer day.

Are Honeycombs as Perfect as They Look?

Charles Darwin was curious about how bees built such perfect honeycombs. He never found out how they did it but considered the ability to be “the most wonderful of all known instincts.”(On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection) But he may have been wrong about instinct.

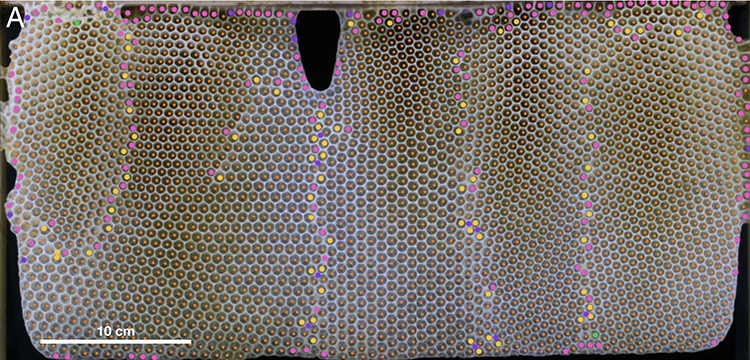

Looking at a honeycomb you wonder how bees make those perfectly uniform hexagonal cells and further wonder how it looks so neat when bees frequently start simultaneously from different sides and merge somewhere in the middle, especially in the wild. The techniques used became more clear in a set of recent studies by Michael Smith and others which used automated techniques to measure cell sizes and spacing. Bees have to accommodate different cell sizes for workers, drones and honey. They do this by manipulating cell walls shapes and fit in 4, 5 or 7 sided cells to fill gaps and merge lines in the comb.

Below: Illustration of the various construction techniques bees use to accommodate different cell sizes and to merge hive sections. Illustration - Brown Bird Design.

Here is a quote from their paper:

Honeybees are renowned for constructing perfect hexagonal lattices, but this paper showcases them as similarly skilled architects when fitting perfect lattices is impossible. Using automated image analysis, we quantified building challenges that bees face during natural construction and the methods they use to solve them. We found that workers preemptively change their building behavior in constrained geometries to make space for larger hexagonal cells, that irregular cell shapes come in regular combinations, and that bees change both tilt, size, and number of walls to meet different building challenges.

Unlike automatons building perfectly replicated hexagons, these building irregularities showcase the active role that workers take in shaping their nest and the true architectural abilities of honeybees. This rich repertoire of building behaviors suggests that there are cognitive processes behind the comb-building behavior of honeybees, not just hardwired instinct.

You may read the entire paper at this link.” - "Imperfect comb construction reveals the architectural abilities of honeybees." Authors: Michael L. Smith, Nils Napp and Kirstin H. Petersen.

Below: This image of an actual hive has been enhanced to show the techniques bees use to merge different hive sections. Cells with red dots in the center are regular hexagonal cells. The merge lines in the hive are noted by cells of a different color. Each different color indicates a cell with a different number of walls or an irregular shape. Photo from Smith, et al. PNAS.

How do Icicles Take Their Shape?

Text and photos by guest contributor naturalist Diana Thottungal.

Have you been curious about why is an icicle shaped like as it is?

When snow falls on your roof, a little bit melts because your house is not a perfectly insulated igloo. [As a side note, the interior of an igloo is not exactly warm. It's just not as cold as the outdoors, being right around freezing temperature while the outdoors may be well below that.] Back to your imperfectly insulated roof. The snow melts. But the air is cold. As it slides down, the melted snowflake starts to refreeze but it doesn't get to form a flake. And it freezes from the outside in.

Although most substances shrink when they go from liquid form to solid, water expands. This has to do with the shape of the individual water molecules. When it's warm enough to be liquid, the molecules are all scrambled together. As it gets colder, they organize into neat little hexagons which take up more space.

The effect this has on icicles is that they freeze from the outside in. And that means that the inside of the icicle can be liquid water and drip down through the center core so the icicle can elongate from the bottom at the same time that it's getting wider on the outside along it's length. (Photo)

Of course, imperfectly insulated roofs are not the only things that can melt the snowflakes on their way down. Since pine needles stay green all winter, they are busy creating a small degree of heat because that's what the metabolism does. Just like a rooftop, there's enough heat to barely melt the snowflake which then refreezes rather than simply dripping off.

It also does not have to be an obviously green leaf because plants with red twigs, such as dogwood, are also busy metabolizing.

They can also form on icicles creating a little branches, although that's pretty uncommon. Another interesting things about icicles is that they have ridges - fairly symmetrical arrangements of bumps and valleys all the way down. Some icicles look pretty different from the others. They don't seem to have ridges. When some scientist tried to figure it out, the results were that any impurity in distilled water produced the standard ridge effect and pure, distilled water resulted in smooth icicles.

One last tidbit: when icicles are exposed daily to the sitting sun they curve away because of the difference between the melting west facing portion and the shade in back.

Much research has been done on icicle formation by Steven Morris at the University of Toronto. This link will take you to a number of his articles on icicles.

Eloise Butler’s issues with White Oaks and Swamp White Oaks

Notes from a century ago - with today’s opinion

In an earlier in time: Eloise was all for planting Swamp White Oak (Quercus bicolor) in her wildflower garden. On November 16, 1923 Eloise Butler wrote from Malden MA to her volunteer helper Martha Crone that she was sending acorns of Swamp White Oak, which were abundant in Mass but known only from the SE corner of Minnesota. She suggested Martha snoop around locally to see if she could find the tree itself.

The curious thing is or the question is - was this a lapse of memory? She had already planted the first one in the Garden in 1917 with stock she sent back from Kelsey’s Nursery in Boxford MA. Then in 1921 she discovered that she already had several in the Garden but had misclassified them as White Oak, Q. Alba. What happened? Was this a thought of a misclassification a mistake and the trees really were Q. alba?

If Swamp White Oaks were there, they must have died out at some point as Martha Crone did not list them on her 1951 Garden Census. In 1958 she planted the species. Susan Wilkins has planted them in 2017. Their future in the Wildflower Garden may be more secure for the following reasons.

Now - into the future: The species does grow here. The Minnesota counties around the metro area have been the western and northern limit of the tree in Minnesota. In Eloise’s time that range was further south. Right now the tree is on the list of Minnesota threatened plants as of “Special Concern.” But with the recent revision of habitat zones by USDA it is more likely the tree will move further north as the metro is now considered zone 5b. Furthermore, estimates of the U S Department of Agriculture’s Northern Forests Climate Hub, made from modeling either low amounts of climate change or high amounts of change, indicate that by 2100 Swamp White Oak will increase its forest biomass by over 20%.

The swamp white oak in central Minnesota, at the edge of habitat ranges, never reach the size of those in more suitable areas. Yet, the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum has several respectable sized specimens; the largest known in Minnesota is in Chisago County at just under 4 feet diameter. Check out the photo of the one from Illinois, and realize that it and the one in Chisago County are only half the size of the US National Champion in New Jersey.

This link is to the new habitat zones: https://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/

This link is to download the Northern Forests Climate Hub report. The species list is on page 21.

Monarch Threatened.

There was another issue with white oaks in 1923 - Monarch almost burned to death. Monarch was considered to be the oldest tree in Minneapolis and was the pride and joy of Eloise Butler as it was in her wild flower reserve. She considered it to be much older than the Park Department forester, who was probably much closer to the mark. Skaters started a fire on Birch Pond on December 12, 1923 and it kindled nearby dry vegetation and burned up the hillsides, burning 2,000 recently planted evergreens and almost reaching Monarch.

Park Keeper Carl Erickson fought the fire until exhausted but with the help of the fire department, got the fire contained. Considering the age of the tree, this was not Monarch’s first brush with disaster by any means. In 1912 Eloise had tree surgeons remove a number of dead limbs and reinforce the rotting trunk. It was spared from a fiery death in 1923, only to be ravaged by a tornado in 1925 and finally met the end in 1940.

Read the entire Monarch story here.

Below: Eloise Butler with Monarch, July 24, 1924 photo in Minneapolis Star.

Photo Note

Photos that are credited with a "CC " caption are used under Creative Commons license for educational purposes. The letters and numbers, such as "CC-BY-SA 3.0" refer to the license type. These photos may be used by others only for free educational purposes so long as credit is given to the original author whose name precedes the license type. You may learn all about the requirements on the Creative Commons webpage.

Previous articles

November 2023 - The ESA at Fifty

November 2023 - Do Plants Hear?

November 2023 - Eloise Talks to Plants

November 2023 - The Rarer Rubus Compared

September 2023 - Friends Annual Meeting

September 2023 - The Wildflower Garden in October

September 2023 - Fall Gardening for Bees

September 2023 - The Wildflower Garden Perimeter Changes

August 2023 - School Classes in the Garden

August 2023 - The Wildflower Garden in September

August 2023 - Beneficial Wasps

August 2023 - Black Saddlebags

August 2013 - American Lotus in the Garden

July 2023 - Friends Annual Meeting Guest Speaker

July 2023 - The Wildflower Garden in August

July 2023 - The story behind the name - Riddell's Goldenrod

July 2023 - Fruit for rooters

July 2023 - Happenstance at the welcome kiosk - A woman walks by . . .

All selections published in 2023