Twigs and Branches - 2022 September-October.

A web of present and past events

These short articles are written to highlight connections of the plants, history and lore of the Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden with different time frames or outside connections. A web of intersections.

Propagation of the species by mechanical explosive tension - October 2022

A visit to the Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden offers many opportunities to observe and learn about native plants but one such opportunity to difficult to observe - - that is - how some of our Minnesota native plants use explosive means to renew the species.

A plant’s life cycle goes through flowering, pollination, seeding, and die back; with many plants that is all within a growing season. Perpetuation of the species of most flowering plants depends upon pollination and reseeding and many are the means of achieving that. Instead of relying on the wind or birds or animals to scatter seed beyond the parent, several adaptions have evolved to provide distance and better changes of survival.

Seed dispersal

First we look at seed propagation by the method known as explosive dehiscence which ballistically ejects seeds from the mature seed capsule. Many species in the pea family do this, such as Lathyrus venosus and Lathyrus palustris. The seeds are arranged in two rows in a long slim capsule which, when mature, splits open along a longitudinal seam and twists, ejecting the seeds.

Below: 1st photo - An immature pod of Lathyrus palustris. 2nd photo - the mature pod of after splitting and twisting, having ejected most of the seeds.

In the Touch-me-nots (Jewelweeds) the mechanical energy is stored in the soft green cell walls of the pod, which when touched, collapse and twist within 4 ms (mille-seconds) and eject seeds to an average distance of 1.5 meters. (1) Children in the Wildflower Garden love observing this.

Below: 1st photo - the maturing seed pod of Spotted Touch-me-not (Impatiens capensis). 2nd photo - The coiled and twisted remains of the seed pod walls after the explosive dehiscence.

The Witch Hazel (whose seeds mature in the following year) has a seed capsule that uses mechanical energy created when the capsule, maturing from the wet to dry stage, expands in one area and contracts in a different area of its tissue, putting pressure on the base of the capsule which has a soft fleshy area and on the enclosed seed, which then explosively ejects at a very high speed a considerable distance. The snapping sound that is heard occurs at the instance of seed release. Our Garden species, Hamamelis virginiana has been reported to eject seeds as far as 6 meters. A research study (noted below) using Hamamelis mollis gives details of how the process works. H. mollis ejects seeds at the seed of a rifle bullet.(2) Both Thoreau and Teale have written about their experiences with this snapping release.(3)

Below: 1st photo - open Witch Hazel seed capsules. 2nd photo - Diagram of the opening time of H. mollis, going from a wet capsule to a dry capsule. Diagram from Royal Society Report.(3)

Other species of plants that use this ballistic dispersal mechanism include wild violets and the wild geraniums

Pollen dispersal

Next we look at flower pollination achieved by a similar mechanism. Our example is out native Bunchberry, Cornus canadensis, which was indigenous to the Wildflower Garden and survived until the late 1980s when habitat changes caused its loss.

Bunchberry stamens with the pollen on their anthers are shaped like medieval catapults. The petals spring open within 0.2 ms and the stamens accelerate upward at a force of 2,400g and propel pollen into the air, up to 10 times the flower height, where even a light breeze will carry it to other plants to insure cross-pollination. This flower opening, at less than 0.5 ms is believed to be the fastest flower opening of any plant and is considerably faster that the seed release of the Touch-me-nots detailed above.(4) ❖

Below: Video frames of Bunchberry flower expelling pollen in 1.0 ms. Source - A record-breaking pollen catapult. Nature 435:164.

Photos: G D Bebeau or as credited. Text by G D Bebeau.

Notes and additional reading:

(1) Research study of Touch-me-not seed dispersion. (pdf)

(2) Research study of Hamamelis mollis, Royal Society Publishing (pdf).

(3) Witch Hazel experiences of Thoreau and Teale.

(4) Research study of Bunchberry pollen dispersion - A record-breaking pollen catapult. Nature 435:164.

A census of a small plot of land - October 2022

Have you ever counted plant species on a small plot of land -species that were not purposely planted? It is a reality check on how diverse nature can be. Try it on a patch of ground that is not cultivated. This writer selected a smaller area, no more than 12 x 90 feet on the edge of private property that was cleared ten years ago of a buckthorn thicket. Since then 25 native plants have made appearances not counting what we usually call weeds.

If you select an area that has been purposely planted the breath of species that can be supported by a small area is immense. The Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden is a prime example.

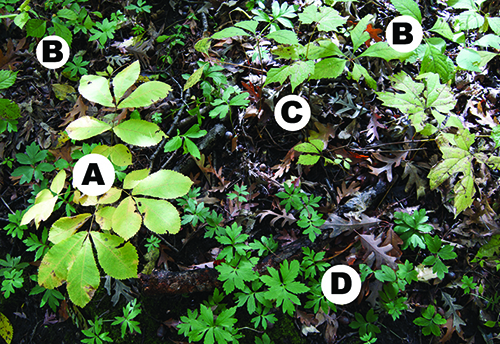

Below: In this example from the Garden in 2018 in a very small area three feet wide are indentifable by the leaves (A) Bitternut Hickory (B) Woodbine, (C) Wild Grape, (D) Virginia Waterleaf. Photo by Betsy McNerney.

In 1951 Garden Curator Martha Crone made the first census of the entire Wildflower Garden since Eloise Butler’s 1907 “census of the most obvious inmates of the Reserve.” The 1951 work listed 787 forbs, shrubs and trees, and excluded grasses, sedges, mosses and fungi. You will find her census on our website.

In 1957 Crone did made a census of a 100 x 160 foot area of the Wildflower Garden. She listed 160 species, many of which had been planted in the years since the Garden’s founding, but it showed the diversity a small plot of land could sustain. (View her list here - pdf).

Below: In this photo is the area north and west of the Garden office that Martha Crone used for her 3/8's acre 1957 census. Photo by Martha Crone

The Garden has updated its census much more frequently in recent history. In 1980 the Friends presented a set of proposals to the MPRB about the development of the Wildflower Garden. One proposal was for a census and in 1986, working with Mary Maguire Lerman, MPRB Coordinator of Horticultural Programs, the Friends funded the hiring of Barbara Delany to do the first census since 1951. In recent years Curator Susan Wilkins has updated the census much more frequently resulting in Eloise Butler’s “most obvious inmates of the Reserve” establishing a record of their continued significance.

Note: Eloise Butler’s quotation is from her 1926 writing Trees in the Wild Garden.

The Garden in late October

The autumn colors at Eloise Butler are never the same from year to year and yet historically, all the years rhyme. Here is a pictorial tour of autumn scenes from 2020 and back to 1950.

#1 Below: The Martha Crone Shelter in the woodland. Photo by Bob Ambler as published in The Fringed Gentian™ Vol 68 no. 3 in 2020. See photo of the shelter in 1950 in the previous article about small plots.

#2 Below: The entrance area of the upland. Photo by Bob Ambler as published in The Fringed Gentian™ Vol 67 no.3 in 2019.

#3 Below: The Early Birders group in the upland near the central white oak. Photo by Bob Ambler as published in The Fringed Gentian™ Vol 66 no.3 in 2018.

#4 Below: The upland central hill with the white oak in more brilliant colors in 2014. Compare to photo #7. Photo by G D Bebeau.

#5 Below: Oak and Aspen on the border between the upland and woodland in 2014. Compare to photo #6. Photo by G D Bebeau.

#6 Below: Oak and Aspen on the border between the upland and woodland in 1957. Note the same aspen as in photo #5. The fence was removed in 1993. Photo by Martha Crone.

#7 Below: Photo from the same day as #6 but to the right with mush smaller Oaks on the central hill. Photo by Martha Crone.

Final fall thoughts:

“In southern states, spring and summer bring a greater abundance of flowering trees and shrubs than in the north. But it is only farther north or in the mountains, where autumn brings sudden plunges of the mercury when evening comes, that we find the full splendor of the colored leaves of fall. On such a day as this everything is beautiful and pensive at once. There is a hint of sadness in the transient glory of these soon-departing colors. This is the culmination of the beauty of our northern year. Now in a relatively few days, in a comparatively swift retreat, will come the rain of colors as, dropping singly or descending in showers, the leaves drift down.” [Edwin Way Teale from A Walk Through the Year.]

Eloise Butler gives advice to gardeners on fall garden cleanup

Prologue: After the heavy frosts and before the kindly snow covers up in the cultivated gardens the unsightly bare earth – suggestive of newly made graves – and the dead bodies of herbs, and the tender exotics, stiffly swathed in winding sheets of burlap or straw, awaiting the spring resurrection, I turn with pride and relief to the wild garden, whose frozen ruins are graciously hidden by the shrubs, which then enliven the landscape with their glowing stems and fruits.(1)

Fall work to avoid: My wild garden is run on the political principle of laissez-faire.

1:Fallen leaves are not raked up unless they lie in too deep windrows and are likely to smother some precious specimen; but are retained to form humus.

2: But the tall dead canes of herbs like Joe-Pye Weed and wild golden glow, which are allowed to stand during the winter to protect the dormant vegetation beneath, are remove from the meadows in the spring for a clear view of the clumps of marsh marigolds, trilliums, etc.

3: I also gather and burn all fallen branches, and in the fall while the late flowers are still blooming, all unsightly evidence of decay.

4: Of course, I do not allow at any time any outside litter to be brought in - - not the tiniest scrap of paper, or string, or peanut shell.

5: The great mass of herbaceous plants, as asters, goldenrods, and most composites, I admire in their fluffy state, after they have gone to seed.

Fall work to be done:

1: Some species, however, are to me the reverse of ornamental in old age. These are snipped to the ground or torn up by the roots and reduced to ash. Red Clover is one of the offenders. It becomes unkempt and scraggly; and the stalks of the common milkweed that are without fruit, after shedding their leaves, turn black and look like long rat tails.

2: Touch-me-not, Impatiens biflora [now I. capensis] and I. pallida, collapse with the first frost and cumber the ground with a brown slime; and wood nettle, Laportea canadensis, is smitten as with a pestilence.

3: A few specimens of stingers and stick-tights are permitted on the grounds. Laportea is a persistent spreader and sometimes gets the upper hand, busy as I am with many other things. In the fall I grub it out and plant something else in its place.(2)

Last request: By all means leave some grasses and sedges unmown. They soften hard edges, and nothing is lovelier in winter than their waving plumes, transfigured at times with hoar frost, ice crystals or snow.(3)

NOTES:

(1) taken from “The Wild Botanic Garden in Glenwood Park, Minneapolis.” Article published in Bulletin of the Minnesota Academy of Science Volume 5, No. 1. 1911.

(2) “Garden Principles - 1920” taken from Annals of the Wild Life Reserve.

(3) taken from “Cultivation of Native Plants” - Published in The Minnesota Horticulturist, Volume 40, No. 10, October 1912.

Now in or coming to a freshwater pond or lake near you! - September 2022

Another cattail is in the water. It was not so long ago that our marshes and wetlands were invaded by the Narrow-leaf Cattail, Typha angustifolia, which is not native to the lower United States, but to Canada. Down here in a more inviting environment it became invasive. It is found in all but 19 of Minnesota’s 87 counties. In some marshes, it predominates. Like many plants that run amok, it was frequently planted years ago when the long-term effects were not realized. Even in the Wildflower Garden, Eloise Butler introduced the species in 1913 and planted more in several years thereafter. Garden Curator Susan Wilkins and staff have removed them as occur but in many local Twin City marshes, they can be seen predominating over our native Common Cattail, Typha latifolia.

Now we have a new kid in the marshes in Minnesota - a cross between the previous two - Typha x glauca Godr. (T. angustifolia x latifolia), and it is overpowering even its invasive parent, the Narrow-leaf.

It dominates to such an extent that the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) states that habitat for waterfowl is being destroyed with a lot of wetlands becoming biological deserts. To counter the invasion the Minnesota DNR since 2017 has been using targeted aerial spraying to eliminate some of the infestations that are so thick that only herbicide can control them. Spraying makes use of a very low flying helicopter (10 to 20 feet up) on calm days, using gps coordinates to get the exact spots. Sites are selected from a submitted list and narrowed down to those where is little danger to adjacent areas. As of 2021, about 9,400 acres had been treated. Funds were provided by the Lessard-Sams Outdoor Heritage Council. Treated areas see the return of open water, wild rice and waterfowl.

Over recent years some newspapers in the upper midwest have reported on this program and how effective it was. [Ex: Dennis Anderson in the Star-Trib, September 20, 2020.]

The hybrid is identified by tiny bracteoles on the pistillate flowers just like T. angustifolia but unlike it mucilage glands are absent from the leaf blade. You will need a hand lens to see these. More visible to the unaided eye are the pistillate spikes that are are medium to dark brown , almost as thick as the Common Cattail, but like the Narrow-leaf, the flowering spike has a gap between the upper staminate flowers and the lower pistillate flowers.

Below: Comparison from left to right:(1) Typha latifolia (flowering) pistillate flowers still green; (2) T. latifolia - note thickness and no gap between staminate and pistillate flowers; (3) T. angustifolia - note thin flower sections and gap, (4) Typha x glauca - note thickness and gap. Photo Rob Routledge, Sault College, Bugwood.org.

Eloise Butler's last Garden project - September 2022

Ninety years ago Eloise Butler fulfilled a decades old wish to have a large sunny aquatic pool in her wild flower garden - a garden which had already been renamed to honor her - the Eloise Butler Wild Flower Garden. This would be her final project.

She wrote in 1932:

Ever since the Native Plant Preserve was started I have wished to have a pool constructed where two small streams converge in an open meadow, the only pool in the Preserve being too shady for aquatics. The hard times gave this joy to me, for a jobless expert did the work for a sum that could be afforded by the Park Commissioners. The pool is about 35 feet long, several feet narrower, and of irregular outline. Indeed, the contour is beautiful. The excavation was made in a dense growth of cat-tails. While digging, the workman saw a mallard duck wending its way through the meadow with a train of four little ones. Hence the name of the pool, as this duck had never been listed before in the Garden.

She then added a little water wheel at the inlet (the south end) and a rustic bridge at the outlet (north end). The bridge was build by Lloyd Teeuwen who was her helper in the Garden and was present at the time of her death in the Babcock house the following spring.

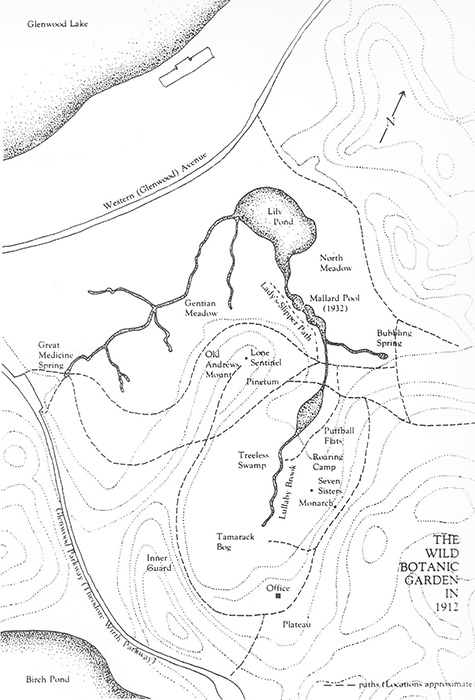

Martha Hellander’s map of the early garden, shows the placement of the Mallard Pool in relation to other features. [This map was created from historical references for her biography of Butler - The Wild Gardener.] That area is now in the open meadow north of the Gardens back gate. Martha Crone tended the pool area until the early 1940’s and then this area was abandoned as part of the Wild Flower Garden in 1944.

Eloise Butler wrote an extensive article about her pool for the circulating bulletin of the Gray Memorial Botanical Chapter of the Agassiz Association, of which she was a member. Her text and our research about the Mallard Pool and the north meadow are found in this document.

The Garden in late September

Asters and Goldenrods are in plentify array in autumn. Check out our photo sheet of most of the species in the Garden.

We want to highlight two goldenrods for special attention.

First is Solidago flexicaulis, the Zigzag Goldenrod, so named for the zigzags of the upper stem. This species will bloom in both dappled shade and in areas with a good amount of sun. It can be a short plant - sometimes only 8 inches high and usually tops out at 4 feet high max. There is a large display of these near the path along the outside of the Garden's west fence. This is the first area outside the Garden that the Friends Invasive Plant Action Group (FIGAG) worked over to clear garlic mustard and buckthorn in 2008. Now you will find many natives are growing in the area. If you plant it at home be careful, the plant self-seeds extremely well.

At the opposite end of the hight scale is Solidago speciosa, the Showy Goldenrod. It is indeed “showy” with its tall unbranched stem and a floral array that can easily exceed a foot in hight. It is a bee magnet and while the root system will form good clumps of plants, it is not an aggressive spreader.

Enjoy them both before while you can.

Many goldenrod species were used by Native Americans for medicinal purposes. Frances Densmore reported that the Minnesota Chippewa used various species of Goldenrod for treating fevers, colds, ulcers and boils. Specifically in regards to S. speciosa, a decoction from pulverized roots was drank to treat lung trouble. A similar decoction was taken for hemorrhage when bleeding from the mouth occurred; another root decoction helped women with difficult childbirth labor. Boiled stalk or root was used as a warm compress on sprains when swelling occurred. These same decoctions of root would be used as general tonics. Dried stalk or root, combined with bear grease formed an ointment.

When October comes don't forget to take walk in the Garden, or Wirth Park or any woods and reflect on the words of Dora Read Goodale:

What does a day in mid-October mean?

Free life, strong feeling, new and quick delight,

All things that are most warm, most rich and bright,

All things that are most sudden, stirring, keen!

The glowing hills, the mountain gaps between,

The sharp, fringed outlines of the wooded height,

The blue, blue sky, the clouds of rifted white, –

The something that is felt and heard and seen!

The genial sun, the strong and breezy air,

The depth of color ere the year shall die,

The sense of life that comes before decay;

The trees that glow ere Winter strips them bare,

The birds that sing before they southward fly,

–All these are in a mid-October Day!

Friends Annual Meeting

At our annual meeting on Sunday September 18, Dr. Lee Frelich, Director of the University of Minnesota Center for Forest Ecology gave a great presentation on "Could climate change turn Minnesota into the new Kansas?” A key part of his presentation was how the changing climate will cause species migration northward. Thanks to those who came or Zoomed in and heard. Garden Curator Susan Wilkins updated everyone on activities at the Garden and the membership elected a new board of directors.