Eloise Butler and the Wildflower Garden

“Being a great lover of nature, an especially of wild flowers and plant life, it was her desire that one part of our park system should be left in its natural condition and devoted to the wild flowers and birds of our state. Under her loving care for many years, this garden has become famous and given pleasure to many." Alfred Pillsbury, President, Board of Park Commissioners, May 5, 1933.

Links below are to bookmarks on this page.

Section I

From Maine to Minnesota

She was born in rural Maine, near Appleton, on August 3, 1851. An interest in botany may have been aroused at an early age by her family's herbal remedies, made at home from their knowledge of local plants. After high school graduation in 1870, she took a position as a teacher in West Appleton, Maine, near the Butler farm, but soon she was enrolled in a Teachers College, the Eastern State Normal School in Castine, Maine, from which she graduated in 1873. After graduation she moved with her parents to Furnessville Indiana where other relatives were already established. [Furnessville was also the boyhood home of naturalist Edwin Way Teale.] That resettlement was not to last long for her, for in September 1874 we find her in Minneapolis. Here she began a long teaching career, principally in Botany, that was to last until retirement in 1911. [Contemporary photos of Appleton, the Butler Farm and Castine.]

During those years in Minneapolis, she pursued her interest in botany by attending classes at the University of Minnesota, collecting, editing and working for certain professors, botany trips to Jamaica, Woods Hole, and the University's new research station on Vancouver Island. In the February 1883 Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club Francis Wolle, writing on fresh water algae, wrote that Eloise Butler "has sent me for microscopical investigation, much more that is new than has any other collector this year." She was a member of the Gray Memorial Botanical Chapter, (Division D ) of the Agassiz Association from 1908 until her death and frequently submitted articles for circulation to chapter members. Some of those articles are referenced later in this text.

In 1911 Eloise wrote about her early years in an unpublished article entitled An Autobiographical Sketch

Back to top of Page

Origins of the Wildflower Garden

As early as the 1880s observant people realized that the development of the city of Minneapolis was incompatible with the retention of native habitat. West of the city in the Saratoga Springs Addition, residents successfully petitioned the new Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners to obtain a segment of that area to preserve for future generations. Named "Glenwood Park" and with adjustments in size over the years, this became what is now Theodore Wirth Park. A small section of this new park was particularly attractive to Eloise and her teacher colleagues. They were having great difficulties familiarizing their students with plants growing in their natural surroundings, as development was wiping out these areas.

A 1907 newspaper reporter wrote: “There was a time, and not so long ago, that some Minneapolis families could pluck these rare wild flowers almost from their back doors, but when too many people took a hand in the culling and the plucking became a massacre, the plants grew discouraged and disappeared.” (pdf copy) This spot in Glenwood Park would be accessible and attractive for that purpose.

Below: Eloise Butler (center) with a Mr. Simmons and unidentified woman studying a natural tree graft near Glenwood Springs, ca. 1900.

As the Board of Park Commissioners (the "Park Board") had done little with the entire park due to lack of funds, this small group decided that something must be done to protect the unique native flora of the small area they had selected. That area included a swampy bog, fern glens, hillsides, upland hills and trees and nearby, the Great Medicine Spring. In April 1907, after a petition from a group of teachers and other citizens (pdf copy of documents) the Park Board was moved to set aside a portion of this area as a Natural Botanical Garden but soon it was known as the Wild Botanic Garden (as the partially visible sign in photo in the next topic states). The initial area designated was only about 3 acres.

Eloise became the most prominent guardian and promoter of this natural space, or as an April 3, 1910 Tribune article put it "practically the mother of the garden," but it was not a paying position nor were the 3 acres considered a permanent set-aside as there was no permanent care arrangements. After 1909, she spent each growing season in the Garden, living with friend Jessie Polley in south Minneapolis from 1912 to 1915 and then she took up lodging just north of the Garden at the J. W. Babcock house at 227 Xerxes Avenue near the Garden where she could walk to her domain. Mr. Babcock owned a photo engraving business at 416 4th Ave. So., Minneapolis. Eloise would room here until her death in 1933. In the fall, the garden closed on September 30th and each year after 1910 Eloise, in mid-October, returned East to 20 Murray Hill Road in Malden, Massachusetts, to stay with her sister Cora. Prior to 1910, while still teaching, she had returned to Malden in July and August each year.

It was originally believed that the Garden, with its naturalist approach, was the first of its kind in North America, but soon after its creation there was an account in the Boston Transcript of a similar garden near St. John, New Brunswick, in Canada that was established in 1899 by botanist Dr. George Upram Hay. It was a two acre "wild garden" on his summer property at Ingleside near Westfield, where he maintained more than 500 species of flowering plants. These were for the benefit of students and those who study plants. It was not a public garden, but the concept was the same. Martha Hellander's research indicates that the Wild Botanic Garden in Glenwood Park was certainly the first natural wild flower garden in the United States and as a public garden, probably the first in North America. Details about Dr. Hay's garden are in this document. Eloise and Cora visited Dr. Hay in 1908.

A document in the archives of the Minneapolis Park & Recreation Board, the successor to the Board of Park Commissioners, titled "Our Native Plant Reserve" by Mrs. John Jepson, gives more detail on the origins of the Garden. Most of the detail in this short history appears to be taken from the notes of Eloise Butler that are preserved in her written documents "Annals of the Wild Life Reserve." Details about that below. This document itself was published in June 1933 following her death, in The Minnesota Clubwoman.

Back to top of page

Eloise - the First Curator

A pivotable moment: The spring of 1911 was the last for Eloise Butler to teach in the Minneapolis School System. Since its founding in 1907 the wild botanic garden in Glenwood Park had been in the care of the high school science teachers, Eloise being as one writer put it in 1910 “practically the mother of the garden.” There was no appointed position of control and there was no guarantee that the plot would continue to be available nor were those conditions being addressed. Thus, on retirement Eloise was planning to return to the East Coast where her sister Cora lived unless some permanent arrangement could be made for her to care for the Garden, to be paid, and for the the space to be made a permanent designated wild garden. (1) If not for what followed next, the history we know would not have happened.

On April 5, 1911 the Garden Club of Minneapolis, meeting in the mayor's reception room at city hall, passed a resolution recommending to the Park Board that Eloise Butler be appointed curator of the Garden and that the space be set aside as a permanent wild flower garden.(2) They were joined on June 5th by the Woman's Club in presenting a petition to the Park Board signed by several hundred persons. They stated that Miss Butler was prepared to begin introducing a number of plants to the space to make it representative of the plants native to the state. The Board did not have any opposition to the proposal but required it to go through the committee process.(1)

On June 9 both clubs put the proposal before the Finance and Improvement Committee. (3) The committee approved as did the full Park Board when it met, but the budget lacked funds for a salary, so her salary was to be paid by the Woman's Club until 1912 with the understanding that the new position of curation was to be permanent as was the space. In February of 1912, the Park Board took over the payment of $60 per month for seven months each year as previously agreed and thus a permanent garden was established and Eloise Butler remained in Minneapolis to make history. (4) If not for this intervention the garden may have suffered the same fate as the earlier wild garden of Dr. George Upram Hay in New Brunswick that Eloise had visited in 1908, but which had no provision for its continuance and now no trace of it can be found. 1911 would prove to be a busy year for Eloise.

Below: A collage of the newspaper headlines about these events. Full text at this link.

Promotion: As part of her crusade to raise public awareness of the Garden, Eloise began to write more extensively for publication. As early as 1909 we know she gave talks about the Garden to groups such as one at the Minneapolis Central Library on March 27, 1909. (5) In 1910 she contributed an article to School Science and Mathematics, Vol. 10, 1910, in which she advocated for "The Wild Botanic Garden." Between 1910 and 1918 she put on an exhibit about the Wild Botanic Garden in the horticulture building at the State Fair. It was a large exhibit consisting of 54 species of trees, 84 shrubs and 400 herbs. Over 100 photographs taken by Mary Meeker, many colored by hand, were on display including several large photos of Garden scenes. The exhibit of correctly named wild flowers won the first premium. The photos then went to the public library for display. (6) In 1911 she wrote, in a weekly series, 22 articles about native plants that was published in the Sunday Minneapolis Tribune. She also gave Garden tours. In the following years she published numerous other articles.

You can read her 1911 weekly articles in our Education Archive. In addition, they are also found in Martha Hellander's book The Wild Gardener, along with a large number of her other writings. Many of these are also found in the our Site Archive.

In August of 1913 Minneapolis hosted a convention for the American Florists and Ornamental Horticulturists. Eloise supplied a display of native wild flowers - whichever ones nature deemed to provide at meeting time. (HTML version of her report).

Her January 1914 letter to Parks Superintendent Theodore Wirth - summarizes why the Garden is so important and so enjoyable.

From 1911 onwards Eloise wrote occasional articles for the newspapers about what plants to see in the Garden. She would note in her text that tours could be had by contacting her during the season. Eloise preferred to not have people come to the Garden and wander around, the paths were narrow, precious plants would stepped on, water holes could be stepped into so she had a number of signs erected of the “do not” variety. More frequently newspaper staff reporters would write about the Garden and what could be found there. Fletcher Wilson wrote in 1926 that “the native plant reserve is under the scrupulous care of a little old woman, Miss Eloise Butler. Except for fences and signs it looks like a particularly beautiful spot in the wilds that has remained undisfigured by the encroachment of civilization.” (7)

The Plant Collection

Eloise Butler's governing idea for design of the Garden was as follows:

“My wild garden is run on the political principle of laissez-faire. A paramount idea is to perpetuate in the garden it's primeval wildness. All artificial appearances are avoided and plants are to be allowed to grow as they will and without any check except what may be necessary for healthful living.”

This was soon modified. Martha Crone wrote in her brief 1951 "History of the Eloise Butler Wild Flower Garden": "The original plan of allowing plants to grow at will after they were once established, and without restraint, soon proved disastrous. Several easy-growing varieties spread very rapidly and soon shaded out some of the more desirable plants. An attempt was made to check them, but with limited help, this proved to be a problem."

In those early years the Garden was relatively secluded. Prof. D. Lange, wrote about the extermination of wild flowers in the cities, in the Minnesota Horticulturist of Jan. 1912. He said: The writer knows of one such glen where there are now growing on the space of about three or four acres about twenty-five different kinds of trees, shrubs and vines, half a dozen kinds of ferns and about half of all the species of the wild flowers found in the country. A little stream and a bit of Indian history make the place still more interesting. What a boon this little place would be to the city twenty-five or fifty years hence!”

Below: Here in 1911 we see Eloise, in full dress and hat, using a downed tree to navigate on a visit to the quaking bog, which is close to the Wild Garden. Eloise would source plants there, as would Martha Crone in later years. Photo courtesy Minneapolis Public Library, Minneapolis Collection, M2632J

The enhancement of the garden with the planting of additional native species then gathered full steam in the hands of Eloise Butler. While the peak years for plant acquisition were 1912-1916, the acquisition of and replacement of species was a continuous process as it remains today. Eloise rescued plants from development areas and sourced them from nearby sources such as the Quaking Bog and local street sides. The Quaking Bog is also located in Theodore Wirth Park, on the west side of Theodore Wirth Parkway, opposite the Garden. It is a hidden five acre acidic bog with mature tamaracks shading an under story of sphagnum moss much like the Garden bog was when the Garden was set aside as a preserve.

It was also her practice to import plants not growing in the area that she thought would grow there, even if they were not native to Minnesota. She sourced many plants from nurseries in other states, particularly nurseries she was familiar with from her families home states of Maine and Massachusetts.

What Eloise was thinking of if the space could be made permanent was explained in a long article in the newspaper about the Wild Flower Garden.(8) This may have been a bit of preemptive lobbying for what she wanted. The article highlighted the natural features of the place, and stated that there were already 452 species of herbaceous plants and 51 shrubs in the Garden. She was developing the following ideas:

1. There was no reason to limit the plant selection to Minnesota plants. Everything that could grow here should be tried. This was not the intent of the original petition creating the space. She considered instead that it should be like an arboretum rivaling if not exceeding those famous ones in the east.

2. There should be a building nearby where visitors could rest, find reference books and photographs. In 1915 she would have her own building built right within the Garden.

3. A herbarium should be established. Years later Martha Crone started one.

4. The space needs to be enlarged. It was already seven acres at this time due to requests from the teachers to add more to their care. Eloise was ready to ask for more acreage to be appropriated and that was done when the space for the Garden was made permanent - eventually reaching 25 acres in the 1920s.

With her plan to include all plants native to the area plus those not native that might grow here, Eloise set about the task with gusto. The years 1912 to 1916 in particular were devoted to the expansion of the plant collection. In those years alone 262 new species were introduced plus the numerous additions and replantings of species already present. The introduction of species never abated. Even in 1932, her last full year as Curator, 11 new species were introduced. Work slowed in her later years, but never was the year without new introductions and replantings.

Her sources of plants included the east coast nurseries she was so familiar with from her winter visits to Malden; nurseries in Minnesota, Nebraska, Wisconsin and Colorado; the Park Board nursery located adjacent to the Garden near Glenwood Lake, and her personal plant gathering forays. Returning from one such foray to Bloomington with Mary Meeker in May 1911, their runaway buggy overturned and Eloise spent a few weeks in a hospital with an arm fracture and hip injury. (9)

Protecting the Plant Collection

It was time for a fence: Eloise Butler was the ‘Park Policeman’ of the Wild Flower Garden. To give herself some air of authority she frequently wore a tin peace officers star. In 1912 Eloise included within the text of her annual report to the Board of Park Commissioners the following:

“Another cause for congratulations is the generous extension of the Garden limits by the addition of an adjacent hillside and meadow. The labor of the curator would be materially lightened if the garden were fenced and more warning signs posted. Her work consisted of conducting visitors, exterminating pestilent weeds and protecting the property from marauders. For “ ‘Tis true, ‘tis pity, and pity ‘tis, ‘tis true” that a small proportion of our citizens have not yet learned to name the birds without a gun, or to love the wood rose and leave it on its stalk.” [Nov. 8, 1912].

By 1913 the area assigned to the Wild Botanic Garden was about 10 to 12 acres. A story about the Garden that appeared in the May 3, 1913 issue of The Bellman stated that the Garden have been enlarged 3 to 4 times the original size. Shortly after that, a meadow north of the Garden was added bringing the total area to 20 to 25 acres. [Eloise cites both numbers in later correspondence.] The article in The Bellman is significant in that it is the earliest detailed description of the Garden and it included 5 photographs that are the earliest views we have of the pool in the Garden, the fernery and the large elms that Eloise had named the “inner guard” and the “lone sentinel.”

In order to really secure the Garden from large animals, vandals and people that just wandered in from all directions without regard to where they stepped, it had to be securely fenced and equipped with gates that could be locked. Eloise Butler even resorted to the newspaper on three occasions to state her case for a fence, but the Garden was not protected by any substantial fence until 1924, and then only partially. Although the initial action by the Park Board in creating the Garden called for a fence, there is no positive record that one was ever put up, but if there were a fence, it would have been around the original 3 acres only as the 1907 action stated. A fence was a necessary step to keep out interlopers, "spooners", and destructive animals, such as the neighboring hog.

Eloise had written in a September 18, 1921 article in the Minneapolis Tribune:

"It’s not the wild, voracious mosquito-

It’s not the snooping vagabond dog -

Nor is it the pussy-footing feline -

But it’s the demon surreptitious spooner thats brought the need for an encircling barbed wire fence around the wild flower garden in Glenwood Park to save plants of incalculable scientific value from destruction.

A stray cat will pitter patter into the garden and leave a narrow trail. A dog seeking food perhaps in the shape of a ribbit (sic) will snoop through and leave a wider wallow -

But the spooning couple -

“For destructive properties the army of tussock worms is a piker when compared with the Spooner.”

In 1924 her call for a fence appeared again in the newspapers but with no action by the Board of Park Commissioners Eloise had the fence put up herself. Details on that went on are in this article on Garden fencing.

Today the neighboring hog has moved well away but the white tail deer have moved in and it requires consistent fence maintenance to keep them out. Natural calamities affect the garden as well. In the photo we see Eloise near a stand of birches, many of which were lost in a destructive tornado of June 2nd 1925. In more recent years the loss of many elms to Dutch Elm Disease and oaks to oak wilt has left some areas without the tree canopy that sustained the habitat beneath, resulting in changes in the Garden's appearance and habitat.

How to handle the "errant" visitors

A Minneapolis newspaper article published in 1917 observed this about Miss Butler:

"If any one comes upon her suddenly, at a quick turn in the path, her first thought is to exclaim: 'do not step off the path, be sure to come this way along this foot path so as not to step on those geraniums,' or it might be gentians if it is fall, or bloodroot if it is spring. These flowers are her family."

A particular person who was confronted by Miss Butler was Minneapolis Star writer Abe Altrowitz who wrote in 1964 about his earlier encounters with her.(10) On his first visit on assignment she led him around naming various plants. On his second assignment she was not present so he nosed around. A year later on a third assignment he writes:

I found Miss Butler very much in evidence. Her greeting was a peremptory challenge: “Young man!” The mien and vocal quality were those of a teacher addressing an erring pupil.

“Yes?” I said.

“Last time you were here you strayed from the pathways. You walked where you never should have without being accompanied by the curator!”

She knew of my transgression because of the names I had used in that second story. I believe she knew every blade of grass in that entire garden acreage. There was nothing I could do but plead guilty. Whereupon she gave me a grand smile and told me I could consider myself forgiven, on condition I never transgressed again. [Article copy]

NOTES to Section I:

(1) "Botanical Garden Sought,"

Minneapolis Tribune, June 6, 1911

(2) "Wild Flower Garden Urged," Minneapolis Tribune, April 6, 1911.

(3) "Wild Flower Garden Proposed," Minneapolis Tribune, June 10, 1911

(4) "Miss Butler's Services Kept," Minneapolis Tribune February 6, 1912.

PDF of articles 1 to 4

(5) The lecture was announced in the Star Tribune on March 27, 1909 and was preceded by an announcement about upcoming Library programs published on December 27, 1908 in the Star Tribune.

(6) Article in Minneapolis Tribune, September 9, 1910 and Twenty-ninth Annual Report of the Board of Park Commissioners.

(7) Minneapolis Tribune, May 31, 1926.

(8) "Wild Flower Garden City Park's Feature" Minneapolis Tribune March 26, 1911. (PDF copy)

(9) Minneapolis Tribune, May 25, 1911.

(10) Minneapolis Star, July 23, 1964.

Section II

Martha Crone

About 1918 a young woman named Martha Crone entered the scene. Her connection to the Wild Flower Garden and later to her assistance in founding The Friends of the Wild Flower Garden are linked back to her innate loving response to wild things and their place in the environment. Like most people who devote a passionate lifetime to the pursuit of a certain subject or hobby, she was largely self-taught about wild plants and birds. Her first contact with the Garden was as an inquisitive and persistent visitor, extracting information from Eloise Butler and in turn bringing in specimens and providing assistance to Eloise.

Martha and her husband William, a dentist, lived at 3723 Lyndale Ave. North in Minneapolis. Together, they were avid explorers of plant habitat and especially mushroom habitat. Martha was secretary of the Minnesota Mycological Society from 1926 till 1943 and a member until her death.. Considering the need for large numbers of plants for the developing Wild Flower Garden, the Crones were able to provide good assistance to Eloise Butler in finding sources for wild plants and for rescuing plants from areas where the native habitat was soon to be overrun with development. Winter correspondence between Eloise and the Crones started in the early 1920s and continued to the end.

PDF file of all Butler's letters to Martha Crone.

Naming the Garden

In Eloise Butler's early years at the Garden, she referred to it as "The Wild Botanic Garden" for two reasons. First, she maintained it in a "wild" state, such as the plants might appear in the natural environment. Second, she wanted to establish which plants would grow well in the climate of the Garden, even if they were not native - hence - it was a 'botanic' Garden. This second reason was slightly contrary to the original stated purpose "to display in miniature the rich and varied flora of Minnesota." (1) The first premise has been maintained to the present day. The second was abandoned at the end of Martha Crone's time when it was established that only plants native to the area should be present.

A second name appeared fairly early in Eloise Butler's time - "native plant reserve." Martha Crone and later Ken Avery used the term 'reserve' when speaking of the Garden. In an essay Eloise wrote in 1926 [The Wild Botanic Garden - Early History] she explained why the second name was chosen: “It was soon found that the term “Wild Botanic Garden” was misleading to the popular fancy, so the name was changed to “Native Plant Reserve,” even though she was bringing in many non-native species. Nevertheless, newspaper accounts of the Garden and its Curator from 1913 to 1924 still called it the Botanical Garden of (or sometimes “in”) Glenwood Park. Kirkwood’s 1913 article in The Bellman is titled “A Wild Botanic Garden.”

On June 19, 1929, the Park Board took official action and renamed the Garden the "Eloise Butler Wild Flower Garden," to which was added " and Bird Sanctuary" in 1968 when the Friends of the Wild Flower Garden requested making the name “Eloise Butler Wild Flower and Bird Sanctuary” making the word “sanctuary” apply to both flowers and birds. Note that the Park Commissioners in 1929 used the words "Wild Flower.” Most documents found in later years use the name with "wild flower" as two words until 1970 when "wildflower" came into use. That came about as the result of the 1968 Friends’ request.(2) The name addition was approved in early 1969 but in the transition after the name was officially changed to add that phrase “wildflower” was sometimes substituted for “wild flower.” In 1986 the MPRB officially made it the ‘Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden and Bird Sanctuary’ but with the two words ‘Wild Flower’ condensed to ‘Wildflower’ and the word ‘garden’ reinserted.

The 1931 Birthday Party

Above: A gathering of friends on her 80th birthday, August 3, 1931. From l to r: Miss Alma Johnson, frequenter of the Garden; Mrs John Hadden, a former pupil; Mrs. J. W. Babcock, in whose house Eloise lodged while in Minneapolis; Miss Clara K. Leavitt, fellow teacher; Eloise; Dr. W. H. Crone (behind Eloise); Miss Elizabeth Foss, botany teacher at North H.S.; Miss Mary K. Meeker, former pupil; Mrs. O. F. (Edith) Schussler, former pupil; Mrs Crone (Martha); Mrs. Louisa Healy, former pupil. Photo: Minnesota Historical Society, Martha Crone Papers.

Below: Following the outdoor photo above, the gathering moved indoors to the J. W. Babcock House at 227 Xerxes Ave. where Eloise boarded during the time that the Garden was open. The seating arrangement here is: Left side front to back - Mrs. Louisa Healy, Eloise Butler, Mrs. Schussler, Miss Leavitt and Miss Foss. Right side, front to back - Martha Crone, Mrs. Hadden, Miss Johnson, Mrs. Babcock and Dr. Wm. Crone. Photo: Minnesota Historical Society, Martha Crone Papers.

Eloise sent copies of the birthday photos to the Crones August 14 with this note: "Dear "Cronies". -- I didn't know when you would be able to come into the garden so I am mailing you the snap shots of the joint birthday party. I thought you would (sic) to see how very English Dr. Crone and Mrs. Babcock look with their monocles as they sit at the table. I think that the out-door print is very good, except that the doctor is somewhat obscured by the dark tree trunk." (PDF copy)

Back to top of page.

The Last Major Project

In the adjacent photo, we see Eloise crossing the rustic bridge at the north end of the Mallard Pool. The year is 1932. She has physically weakened due in part to neuritis and from burns received in 1929 when a heating pad caught fire while she was sleeping. Her doctors advised her that the burns would always be covered with scar tissue, not true skin, so they would always be somewhat uncomfortable. Perhaps the serious hip injury sustained in 1911 never completely healed either. The development of this pool was long on gestation and short on actual building. In her letter to The Gray Memorial Botanical Chapter, (Division D ) of the Agassiz Association for inclusion in the members circular, she wrote in 1932 (3): “Ever since the Native Plant Preserve was started I have wished to have a pool constructed where two small streams converge in an open meadow, the only pool in the Preserve being too shady for aquatics. The hard times gave this joy to me, for a jobless expert did the work for a sum that could be afforded by the Park Commissioners. The pool was quickly constructed by the unemployed man and another (Lloyd Teeuwen) was employed to build a rustic bridge of tamarack poles and planks to span the narrow lower end of the pool. When a mallard was soon seen in it, it became the “mallard pool.” Eloise had planned extensive plantings around the pool and these were completed by Martha Crone in 1933. That pool is no longer within the boundary of the Garden as the area was abandoned by 1944, but the Garden does contain a pool, in the same place where Eloise originally created one in the Garden's first years, which has acquired the same name.

More details about the wetland and the pools will be found in our article "The Wetland at Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden" and in particular in this detailed article about Open Water in the Wetland.

Back to top of page.

The End of a Long Career and the myth of her death in the Garden.

1932 was Eloise’s last full year as curator. She wanted to retire but had been unable to find a replacement.(4) While at Malden she wrote what would be her last letter to the Crones on January 11, 1933 in which she thanked them for the Christmas gifts they had sent and she attached copies of correspondence from Pearl Heath Frazer which she wanted the Crones to keep for her as she (Eloise) may want to show it to Mr. Wirth upon her return to Minneapolis. The correspondence was about Mrs. Frazer taking on the job of Curator so that Eloise could retire. Eloise had sent a letter, at the request of Parks Superintendent Theodore Wirth, to Mrs. Frazer on September 29, 1932, explaining the job. Mrs. Frazer had replied to Eloise that that was not the sort of job she was interested in. (pdf of Eloise's letter to the Crones).

In that letter to Mrs. Frazer she lays our her plan: "My aims are only to secure the preservation and perpetuity of The Preserve, as well as its helpfulness to students of Botany and lovers of wild life. When these aims are secured, I am ready to fade out of the picture and will promise that not even my ghost will return to haunt the premises." [See above pdf.]

Eloise returned from Malden to her Minneapolis lodgings at the Babcock house (located just east of the Garden at 227 Xerxes Ave. North) on April 3 1933. Mr. Babcock notified her Garden helper Lloyd Teeuwen, that she had returned but Eloise wanted to rest a few days after the long train ride from the east coast as she was “not used to walking a lot yet.” Several days later Lloyd came to the house and carted down to the Garden office the assortment of books from her library at Babcocks that she wanted in the Garden and also the Garden’s tools which were kept in the Babcock carriage house over the winter. She had about 300 books at the Babcock house and about half went down to the office. Then Lloyd and Eloise took the first walk of the year through the Garden where Eloise inspected all the areas to see what was what. She walked very slowly so Lloyd kept behind her to not outrun her. Eloise remarked how enthusiastic she was to be back outside where she could do something because in Boston nobody wanted to do anything. (6)

On the wet morning of April 10, 1933, following an overnight rain, she attempted to reach the Garden from Babcock's. She apparently suffered a heart attack and got back to Babcocks. A doctor was summoned but nothing could be done and she soon passed away on the couch in the entryway of the house around 3:15 PM. Her funeral was on April 12th, 12:45 PM at the Lakewood Chapel. On May 5th, her ashes were scattered in the Garden as had been her wish.

The myth that she died in the Garden: It is frequently misstated that she died in the Garden and some boys found her there. There is the account of one present at her death at the Babcock House where the doctor was attending her and there is also the coroner's report. It is clear from everything that she died at the Babcock's house. We shall try to clear up how she got there.

Perhaps this romantic myth of her dying in the Garden has some origin in Theodore Wirth's April 19th letter announcing her death when he stated "(she)....had suddenly died in the park while on her way to her domain." Or perhaps it is a misreading of the reports of her death in the newspapers. For example, the Minneapolis Journal reported on April 11th (speaking of woodland flowers) that "Miss Butler died yesterday in their midst." The article further says that "she was found leaning against a stump near a little by-path." That last part is believed to be true, (as Wirth's statement that she died "in the park on her way to her domain" may be partially true) as it is known from witnesses on April 10 that she attempted to go to the Garden. Some newspaper accounts and Martha Hellander's research indicate she was found on her way to the Garden and was helped back. But she did arrive back at Babcock's house. The newspaper incorrectly identifies the Babcock house as J. W. Butler's house. (5)

First: The testimony of Lloyd Teeuwen: The only eye-witness account of her death by anyone still living was given by Lloyd Teeuwen on May 4, 1988 in a recorded interview with Martha Hellander while Hellander was researching material for her book The Wild Gardener. Teeuwen was a Garden helper for Eloise, beginning when he was 13 or 14 years old. It was he who build the rustic bridge on the Mallard Pool. It was six years later when on that wet morning of April 10th, he came to the house to help Eloise down to the Garden, as he always did when the paths were wet and muddy. He asked "do you want to go down there and try it." "No" she replied, "I don't think I want to go down there now, maybe a little later if it stops, maybe we can go down there." Lloyd then went down to the Garden where he was working on some brush. He believes she may have attempted to negotiate the path herself but states "They didn't find her anywhere, she got to the house herself." Mrs. Babcock had told Teeuwen that Eloise had gone out but was only gone a short time when she returned. "She'd come in and Mrs. Babcock says 'She said she didn't feel too good.' " (6)

When Lloyd returned to Babcocks from the Garden Eloise was there and his report of her death is as follows: "When I came in there, the doctor was there, and she was laying in the Living Room; they had what they call a little entrance way, like a vestibule, and it had a black leather couch in it and she was laying on it. [Hellander - In the Babcocks house?] Yes, you came in the front door - the doctor had come in it - I don't remember his name at all any more - and he was checking her out like that [Hellander - was she still living?] She was still living, but she was, ten minutes later, he says (the doctor), 'she's gone.' " (6)

Second: The Minneapolis Coroner's Report: This report states that she left the house at 1 PM and was found around 2:10 PM in the garden near the house. "She was unconscious and carried on a cot into the house by Martin Olson and Walter Ludvig - she breathed deeply - did not regain consciousness and died in one hour later." The doctor present was Dr. Arthur Mann.(7)

The Coroner's report supports the statement that she was found in the park and brought back. It states she did not regain consciousness. As the doctor was not present for the entire episode it is not possible to negate Teeuwen's testimony about what Mrs. Babcock said. How those two men (or boys?) happened to be around is unknown, nor how they obtained a cot - perhaps from Babcock's?

The conclusion about her death is that she did go down to or toward the Garden and that she died at the Babcock house as both Teeuwen and coroner's report testify. The words that Teeuwen used in speaking to Martha Hellander were from his memory of an event 55 years prior, so some parts of it may not be 100% accurate recall.

Theodore Wirth Announcement.

"For a full quarter of a century, her useful life has been spent in a labor of love..." Theodore Wirth, Superintendent.

It is not unusual that the accomplishments of an individual are more clearly understood after that person has passed on. While certain people are "in-the-know" about what an individual is accomplishing, it is only after death, when congratulations are too late that the rest of world becomes aware of the qualities of the individual whose life is now past. Theodore Wirth, Superintendent of the Minneapolis Park System, was probably the first to craft a brief but informative statement about the role Eloise Butler had taken on and played with such accomplishment. His letter of April 19, 1933, addressed to the Board of Park Commissioners informed them of her death and of her accomplishments. The letter announced the date for the remembrance ceremony to be held May 5th and also got the ball rolling on the commemorative tablet that was placed one year later.

Complete text of Theodore Wirth's April 19, 1933 letter.

The commemorative tablet that Wirth mentioned was also reported in the newspaper in an article announcing the upcoming ceremony. The Minneapolis Tribune stated on May 4 "Near the little cabin that served as her office the commissioners will stand about and scatter her ashes among the flowers she loved. They will plant a young oak in her memory, knowing that before long her former botany students will have subscribed enough for a bronze tablet to commemorate the occasion and to perpetuate her name."

The article reported that the commissioners visited the Garden on Wednesday afternoon (May 3) "They inspected the growths, the cabin, paused at the bird bath of stone, noted the bird houses, and agreed that the wildflower garden was a place of serene and peaceful beauty." [pdf of article]

Remembrance Ceremony

On April 28, 1933, Superintendent Theodore Wirth wrote to the Board of Park Commissioners (pdf copy) that the Remembrance Ceremony for Eloise Butler was to be held at 4:00 o'clock in the afternoon on May 5, 1933 in the Wildflower Garden. He stated that he had secured good specimen of a Pin Oak to be planted and made the suggestion that

That every member of the Board participate in the planting of the tree, and that the President of the Board perform the rite of spreading the ashes.

About 100 people attended the ceremony. Mr. A. F. Pillsbury, President of the Board of Park Commissioners, officiated. The Pin Oak tree acquired by Superintendent Wirth was planted in her honor and her ashes were scattered within the area, as had been her wish. (The Pin Oak is difficult to establish there and was subsequently replaced with another.) Use this link to see the full report of the Ceremony: May 5, 1933 Remembrance Ceremony.

Poem for Eloise

Dust we are, and now to dust again

But gently blown throughout the glen

Which was your alter and your shrine

Wherein you gave a life of tenderness all thine

In every nook your footsteps trod

The plants you loved belong to God

And in his keeping they are ours

The trees, the shrubs, the blessed flowers

And still your soul, on guard, will stand

Against the touch of vandal hand.

From Martha Crone's Notebook, Martha Crone Collection, Minnesota Historical Society

Memorial Tablet Dedication

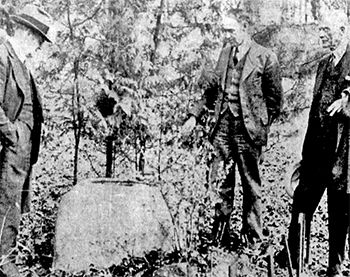

At the end of the path from the front gate of the garden to the Martha Crone Shelter will be found a large granite boulder bearing a dedication to Eloise Butler. The boulder was placed the year following her death in front of the Pin Oak tree that was planted in her memory. On the boulder is mounted a bronze tablet, dedicated on Arbor Day, May 4th, 1934. The oak is no longer there, but the boulder was sheltered by a large Leatherwood shrub until 2022 when it died - another plant she had sought out for the Garden. Her "occult" experiences in finding this shrub were described in this writing.

Commentary, historical documents, and photos of the dedication: Butler Tablet Dedication.

Below: Newspaper photos from day of dedication. Click on photo for a larger image.

Notes to Section II

(1) (pdf - 1907 petition documents)

(2) Notes and board minutes of Friends of the Wild Flower Garden from 1968.

(3) Agassiz Association : The Agassiz Association was founded in the late 1800‘s to be an association of local chapters that would combine the like interests of individuals and organizations in the study of Nature. The Gray Memorial Botanical Chapter, (Division D ) of the Agassiz Association was the chapter that included the middle west. However, after 1901 it was largely defunct and only the Gray Memorial Botanical Chapter, with the same divisions, was still active. Eloise Butler made a number of contributions to it about her garden and about wild flowers. She was a member from 1908 until her death. Various contributions from members were periodically grouped and circulated by post from one member to another. There was no printed published journal at this time. See "History of the Gray Memorial Botanical Association and the Asa Gray Bulletin" by Harley H. Bartlett in the Asa Gray Bulletin Vol. 1, No. 1, January 1952, Ann Arbor Michigan.

(4) Letter to Pearl Fraser, September 29, 1932.

(5) Minneapolis Journal April 11, 1933 (pdf image)

(6) Interview with Lloyd Teeuwen, May 4, 1988 by Martha Hellander. Tape and transcript in the Martha Crone Collection, Minnesota Historical Society. Lloyd passed away on June 16, 1992.

(7) Report of the Hennepin County Coroner, April 10, 1933. Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, MN. (PDF)

Section III

Notes on the Curator's Office and Shelter

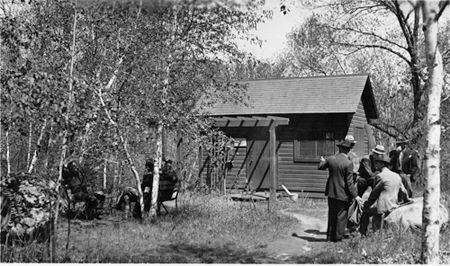

In this photo we see a more complete view of the original curator’s office. Click on the photo for a larger image. This building, located on a flat plateau in the woodland part of the Garden was first erected in 1915 based on Eloise's design. It had two rooms and served as office, tool room, visitor center and for everything else. Prior to that date there was no shelter in the developing Garden, just a tool shed. The year of this photo is 1935. You will notice the small sign visible to the left of the door - it reads “Office of the Curator - Wild Botanic Garden,” even though that name had been discarded for some years prior. The Garden was officially renamed the “Eloise Butler Wild Flower Garden” on June 19, 1929.

In this photo we see a more complete view of the original curator’s office. Click on the photo for a larger image. This building, located on a flat plateau in the woodland part of the Garden was first erected in 1915 based on Eloise's design. It had two rooms and served as office, tool room, visitor center and for everything else. Prior to that date there was no shelter in the developing Garden, just a tool shed. The year of this photo is 1935. You will notice the small sign visible to the left of the door - it reads “Office of the Curator - Wild Botanic Garden,” even though that name had been discarded for some years prior. The Garden was officially renamed the “Eloise Butler Wild Flower Garden” on June 19, 1929.

The man seated at the right is sitting on the boulder bearing the memorial plaque to Eloise Butler that was dedicated in May, 1934. The men on the left are sitting on wooden "settees" that were replaced in 1960 by Kasota Limestone benches with a dedication to Clinton Odell. For more photos of both the old office and the new Martha Crone Shelter see "The Old Office Replaced". Photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society, MH5.9 MP4.1 r356

That old useful structure, becoming more rustic as each year passed, was finally replaced in 1969-70 with the current Martha Crone Shelter when the Friends of the Wild Flower Garden took on the major challenge of having a new structure designed and built. With much more room for the Garden Curator and naturalist staff, display areas, a fireplace and attic storage, this building still serves well today. The Garden Curator’s tool room has long since been relocated to a storage building/work room at the top of hill above the shelter and near to the front gate.

That old useful structure, becoming more rustic as each year passed, was finally replaced in 1969-70 with the current Martha Crone Shelter when the Friends of the Wild Flower Garden took on the major challenge of having a new structure designed and built. With much more room for the Garden Curator and naturalist staff, display areas, a fireplace and attic storage, this building still serves well today. The Garden Curator’s tool room has long since been relocated to a storage building/work room at the top of hill above the shelter and near to the front gate.

Photo: The Martha Crone Shelter which replaced the old "office" Click on photo for a larger image. Photo © 2007 Friends of the Wild Flower Garden

Back to top of page

Eloise Butler's Writings

Once the Garden was established in 1907, Eloise began writing about it. A number of her essays were published in various periodicals, newspapers and also circulated to members of the Gray Memorial Botanical Chapter, division D, of the Agassiz Association of which she was a member from 1908 until her death. Those circulars were circulated among members by postal round-robin circulation and may be the principal reason why, as a newspaper article stated, that she was more well known elsewhere than locally. The Agassiz Association after 1901 was largely defunct and only the Gray Memorial Botanical Chapter, with its several divisions, was still active and remained so until 1943. Details on the Association and Eloise's affiliation are in this article.

She also included much information in The Annual Reports of the Board of Park Commissioners. Over the years she wrote a number of columns for the local newspapers including a series of 22 in 1911, published in the Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, that described various plants in the Wild Botanic Garden. All 22 articles are available in html format in our Educational Archive, as are a number of those published in other venues. She also wrote many shorter articles that were never published. These essays began with a short autobiography and progressed to describing events that occurred in the Garden or on plant hunting excursions; some were observations on the characteristics of plants. Particularly memorable were her recounting of finding the Walking Fern and the White Lady's-slippers and what happened when her hat caught fire. Her intent was to group them into several series under the titles such as "Annals of the Wild Life Reserve." A number of these articles will also be found in the Archive.

Eloise Butler Biography.

A complete biography of Eloise Butler was written in Martha Hellander’s book The Wild Gardener, published in 1972. While it is now out of print and not available from The Friends, information on Martha Hellander and how she created this book plus photos and information on her research in Maine on the Butler Family see This Article

Book, The Wild Botanic Garden - 1907-1933. This is a companion volume to Martha Hellander's biography of Eloise Butler. It details the events of each year of Eloise Butler's tenure as Curator of the Garden and is available as a downloadable PDF File. (2018)

Eloise Butler and Claude Monet

A short article on some common themes between these two gardeners.

Here are some links to other sites with information on Eloise Butler.

The first link takes you to the Minnesota Historical Society where there is a short biography of Eloise Butler, Martha Crone and also a complete inventory of documents that the Historical Society has in it's collection on Eloise and the Wildflower Garden.

Minnesota Historical Society

Printable PDF file of this page.

©2012 Friends of the Wild Flower Garden, Inc. Quotations of Eloise Butler are from her various writings, from The Wild Gardener, by Martha Hellander, North Star Press Inc., 1992, used with permission, from newspaper articles and from documents in the Martha Crone Collection at the Minnesota Historical Society. Photos used with permission of noted source. Text by Gary Bebeau.